-As I write this I’m realizing that this first attempt will, for now, serve only as an introduction to growing potatoes for the purpose of seed. I’ve spent some time on it, and the topic is just too complex to cover thoroughly in one page. In the future I hope to go more in depth on each of these items and offer more information, photographs, and illustrations.-

In this article I’d like to look at some things to consider and techniques to use for growing high quality seed potatoes in a garden or small farm. Growing healthy seed potatoes takes a conscious effort, and is not a byproduct of growing potatoes for food. It is preferable that you start this seed saving endeavor with potatoes that are, to the best of your knowledge, free of disease. For most people this will mean purchasing certified seed; ideally prenuclear seed. This doesn’t mean that you can’t employ these methods on potatoes you already have, but they won’t remove viruses if they are present. Finally, before we jump in, there may be some unfamiliar vocabulary ahead. I have created a potato terminology page to help in this regard.

Disease mitigation

Disease is the main cause of seed potato degeneration, so for growing and saving potatoes it is important that we try to avoid diseases where we can. If soil health is poor, or other environmental stressors are too extreme, the plants will be more susceptible to disease. A combination of good soil health practices, crop rotation, some level of genetic resistance, and the techniques discussed below will give you best results for continued propagation of your potatoes.

Calculating yearly seed needs

Here I make some generalizations to arrive at an estimated amount of seed potatoes needed yearly. In practice, different varieties and growing conditions will yield more or less potatoes. Consider this exercise a starting point, and input your own data when you have it.

- How many pounds of food potatoes do you want each year? 500lb

- Plants grown for food yield ~2lb per plant

- This would require 250 plants to produce your food potatoes.

- How many plants are needed to produce seed?

- Plants grown for seed potatoes will yield ~10 seed tubers per plant

- This would require at least 25 plants to yield seed for your food plot.

- How many plants are needed to produce next years seed plot? 5 choice plants would produce 50 seeds. Any extras could also be used for food production.

- Your needs would be at least 280 seed tubers each year. 250 to produce the 500lb of potatoes for food, and 30 to grow the plants required to produce seed tubers. 30 plants grown for seed production would yield ~300seeds.

- Seed potatoes are ~@2oz each, so this is ~37.5lb of seed total.

Seed plot technique

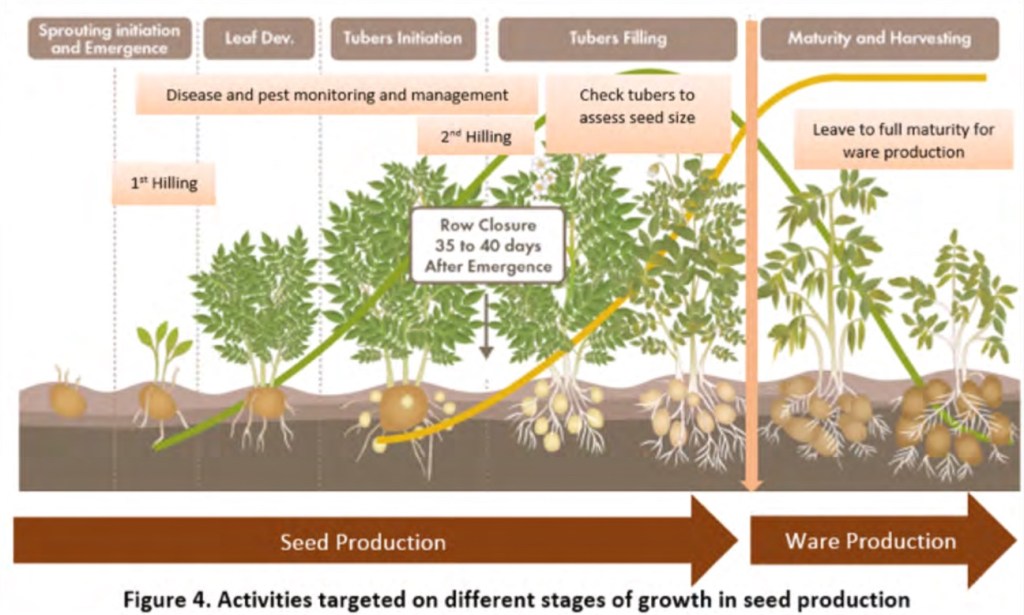

This technique is, at its simplest, growing potatoes for the purpose of seed production as a different plot from your food potatoes. Growing potatoes as seed requires slightly different management, and more stringent screening for unhealthy plants. The seed plot should be isolated from your food plot by some distance. Recommendations vary widely, so in a garden or small farm I would give what space you have, and plant barrier crops (any non Solanaceae) between them. Plants grown in the seed plot should be grown closer together to try and yield a larger number of small tubers. Plant spacing should be around 8” within the row. Hill or mulch the plants as you would normally grow potatoes. Around the end of flowering, begin to dig a few random tubers to monitor their size. When desired tuber size is reached (roughly 80 days after planting) plants should be dehaulmed. Wait two to three weeks after dehaulming to harvest. At this point perform tuber evaluations as you would using positive and negative selection.

Roguing (negative selection)

Roguing is the selection and removal of plants that show symptoms of disease. This technique is best used when starting from disease free seed. If you are starting from tubers that you suspect carry some disease, it may be best to start with positive selection.

Before you begin, it is helpful to familiarize yourself with visual symptoms of local diseases. For the Pacific Northwest there are some great resources that I’ve listed at the bottom of this page. Roguing should take place a week or two after emergence, and again before the plants have all grown together. Observe plants within each variety, and dig up and remove plants that show any symptoms of disease. Try to get all of the plant, roots, and tubers. It is recommended that you add a handful of wood ash to the hole afterward.

Positive Selection

If you are starting with seed potatoes of unknown quality, positive selection may give better initial results than roguing. Positive selection is selecting the best looking plants from a population.

After planting, but before the plants grow together and are indistinguishable from one another, walk your patch looking for the healthiest individuals within each variety. Mark these plants with a stake that will be be visible at harvest. When your plants are ready, harvest your marked plants first, setting the tubers from each plant next to where they were grown. Do not save tubers from plants if:

- Yield is lower than normal

- Tubers show signs of scab, black scurf, or other disease

- Tubers are misshapen

- Tubers are damaged or rotten in any way

- Anything seems off. Be stringent.

Putting it all together

Potatoes are joyfully complicated to manage; there are so many different methods and growing techniques to consider. The information I covered here really only scratches the surface of these methods, so for a more in depth look at any of these techniques I would encourage you to peruse the resources I’ve listed.

Resources

- https://www.chelseagreen.com/product/the-resilient-gardener/

- https://cgspace.cgiar.org/bitstream/handle/10568/76795/1544_PDF.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNABD596.pdf

- https://mtvernon.wsu.edu/path_team/potato.htm

- https://pnwhandbooks.org/search/site/Potato

- http://cipotato.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/TIBen19604.pdf